Re-engaging America in Civic Society: Part II

New Game, Old Strategy

Sports games are dynamic. Conditions change because of weather, new players, or innovations, among other reasons. Successful teams learn to adjust to the new conditions, or, at the very least, they modify their tactics to be more effective. In most cases, new conditions often call for a modified strategy if the game is to be won.

Sports games are an analogy in this case, but an apt one for civil society. Conditions changed with the advent of the smartphone in 2007 and Facebook’s widespread use around the same time. Some corners of civil society adopted new tactics by piggybacking on these tools to stay relevant. Regardless, their voice is lost in the din of ever-shorter competing social media clips and incessantly buzzing smartphones fragmenting our attention and socially isolating us. The unfortunate fact is that most of civil society is still relying on an outdated strategy.

The parent-teacher association in my local district is a case in point. I live in Silicon Valley, the world hub of innovation and technology. The Valley invented the smartphone, perfected messaging, and made touchless, online payments possible. Yet, my local school district relies on mailers, physical flyers sent home via student couriers, and emails to raise awareness for all causes. Of course, many parents express enthusiasm for the well-intentioned causes. But, because of the clunky intermediary systems and processes, participation and engagement falls dramatically from the initiating point of raising awareness to the ultimate goal of attracting volunteers and donations. Alas, when it comes to donation processing, my local school district still relies on physical checks and third-party remittance services like PayPal.

My local school district, as well as countless other local-community organizations, have adopted some new techniques – among them emails and PayPal – but they seem to be oblivious to how the ground rules have shifted beneath them. These well-intentioned, social-fabric-building organizations are losing the game because they are competing with weapons of mass distraction perpetuated by the very tools they have clumsily adopted. They have not adapted their strategy to the realities of the current information and attention age in which we live.

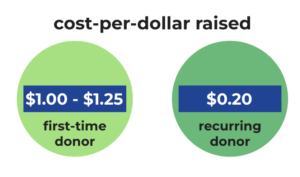

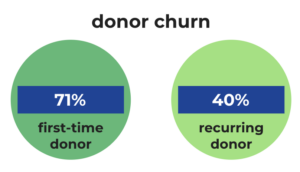

The poor results speak for themselves. Per Affinity Resources, civil organizations spend $1.00 – $1.25 for every new donor dollar they bring in. Luckily, that cost drops to $0.20 for every new dollar from recurring donors. Clearly, the goal is to invest in attracting new donors and keep them as recurring participants. However, civil society is swimming upstream given the churn rates for both new or recurring donors, respectively being 71% and 40% per Blackbaud Institute.

Simply put, civil society’s current tactics are very expensive and inefficient. Because these organizations are being reactive, and per National Philanthropic Trust, they spend 36% of their time and resources fundraising. This distraction is degrading civil society and defocusing it from its core mission: serving the community.

time wasted

New ground rules require a new strategy and better tools.

In part I, I described the current state of the American civil society.